Yo solo intentaba hacer un true crime sobre un asesino en serie de los años 80

Un ordenador antiguo que se congela al abrir un PDF y una IA que pone voz a testimonios de 1986. Así continúa mi crónica sobre la irrupción de la IA en mi trabajo documental y creativo.

Es martes, 28 de mayo, van a dar las 10:30 de la mañana. Estoy en un apartamento de Miami Beach, cerca de Collins Avenue con la 69. Llevo unas semanas aquí, investigando con el equipo de la serie documental en la que estoy trabajando.

Ahora mismo tengo a ChatGPT haciendo esquemas, resúmenes, listas, cronologías… En definitiva, intentando poner orden en un caos de documentos —miles de folios— que le voy suministrando en dosis controladas para que no se gripe, el pobre.

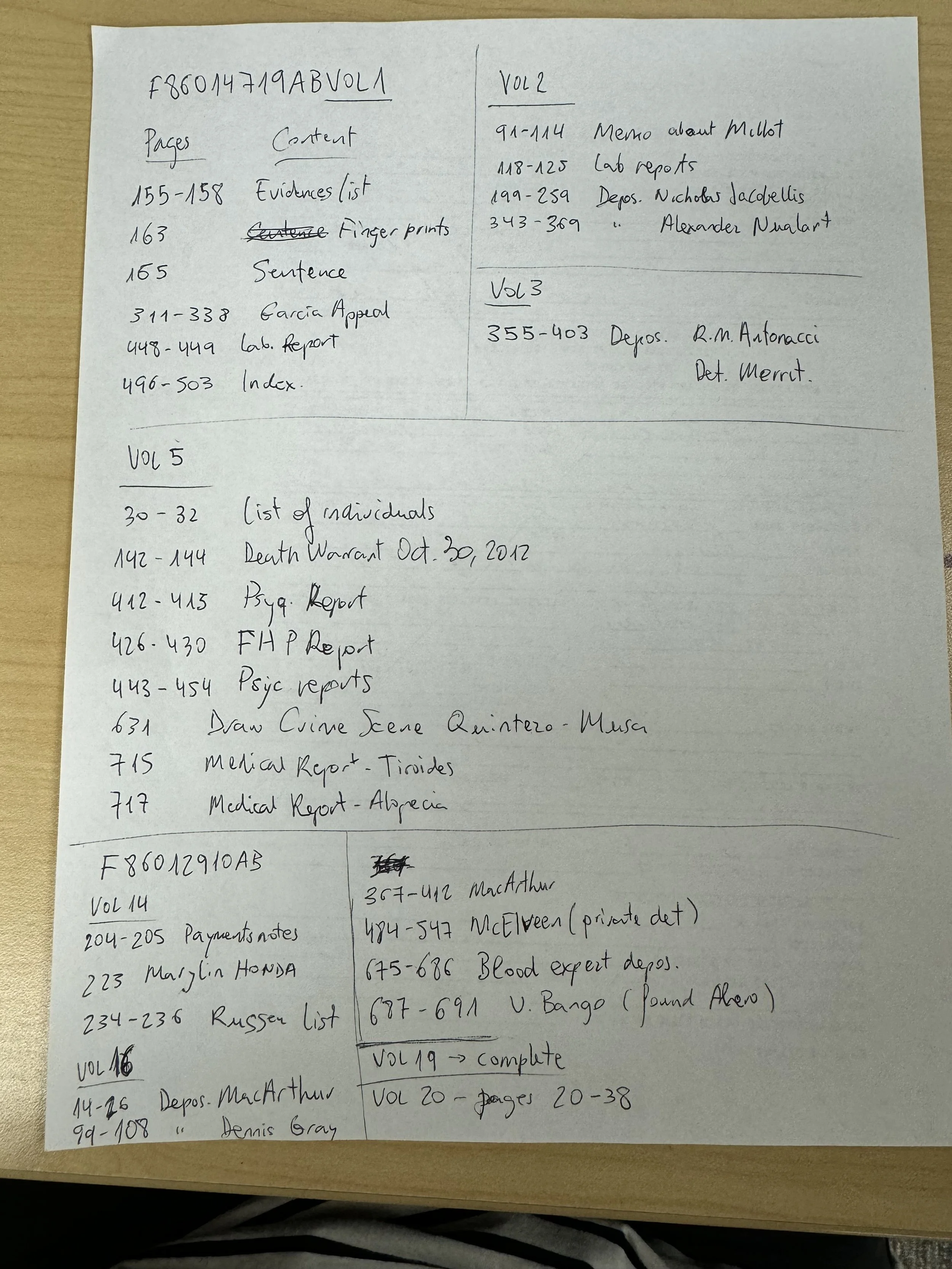

Afortunadamente, la Corte de Miami tenía digitalizado el caso F86012910A. F es de felony y 86 es el año. El expediente está dividido en unos veinte volúmenes de entre 300 y 2000 páginas cada uno. Revisamos el material allí mismo, en un ordenador del Jurásico usando Windows Photo Viewer, página por página. Me riñeron por tener la osadía de intentar abrir Acrobat. Aquella maravilla de 64 MB de RAM se quedó colgada nada más hacer doble clic. Hubo que reiniciar y tocó resignarse a anotar a mano las páginas que nos interesaban de cada volumen.

Luego lo transcribí y lo envié por email al jefe del archivo.

Pasamos varias jornadas haciendo clic, clic, clic, revisando y marcando lo que no era morralla o repetición.

A continuación, el personal del archivo revisó nuestra selección para eliminar información sensible. Quitaron un informe médico que le hicieron al asesino a instancias de su defensa para la última apelación, que no prosperó. Finalmente fue ejecutado por inyección letal en 2012. Pero por favor no violemos la privacidad de sus datos médicos.

El momento verdaderamente surrealista llegó entonces: el personal de archivo imprimió la selección de documentos, los escaneó de nuevo y nos los entregó en un pendrive.

Algunas partes ya se veían regular en el primer escaneo porque los papeles tenían más de veinte años cuando los digitalizaron. Con el escaneo de la impresión del escaneo, el OCR de Acrobat ha hecho lo que buenamente ha podido.

ChatGPT tiene orden global de analizarlo todo y de ir rellenando los huecos con la información de los documentos nuevos que le voy adjuntando. Lo definí así, como tarea transversal, en el prompt inicial del proyecto. No tengo certeza de que vaya a mantener esta instrucción con el tiempo, pero quiero confiar.

Cuando empecé a trabajar con él, pensé: ¿No es mágico? Es mi nuevo mejor amigo. Enseguida descubrí que es un amigo fantasioso. Si no le marcas límites, vuela. Te dice lo que cree que quieres oír. Se inventa cosas. Te miente.

Ahora mismo tiene entre manos una tarea concreta. Le he compartido todos los affidavits de los oficiales de policía que acudieron a las escenas de los crímenes. Son declaraciones juradas bastante detalladas de lo que se encontraron. Le he pedido que extraiga una cronología de todas las víctimas con descripción de las escenas, geolocalización, nombre del oficial y texto íntegro de su declaración. Esto va a ser la base para una secuencia de presentación de los asesinatos. La imagen alternará un mapa de Miami-Dade County, marcando los lugares de cada crimen con zoom-in o zoom-out, y fotos de las escenas. La narración en off será un collage de fragmentos de las declaraciones de los oficiales.

Aquí entra la segunda IA que me está ayudando con este primer montaje del documental: el software de síntesis de voz de ElevenLabs.

La tarea aquí es poner voz a una selección de los textos de las declaraciones juradas. Damos dimensión sonora a unas palabras que ya existen, y que probablemente fueron escritas tras ser pronunciadas entre compañeros de profesión. Recreamos entonces su puesta en voz alta.

La primera vez que generé yo misma una voz me dio cierto reparo. No porque sonara artificial, sino por todo lo contrario. Había pausas, respiraciones, un ritmo casi siempre humano… A veces algún artefacto tipo psicofonía o distorsión me hacía saltar de la silla del susto. Pero lo que me resultaba inquietante al principio era lo real y verosímil de los audios.

Sin embargo, enseguida me acostumbré a trabajar con esas voces que no son humanas aunque provengan de la clonación de voces reales, y que tampoco son robóticas porque su base es una voz humana clonada con matices y texturas. Para no perder la perspectiva, me digo a mí misma que estas voces son un medio para transmitir un mensaje, como lo serían las de unos actores si la secuencia fuera parte del montaje final y esas voces llegaran a grabarse.

Al no ser nativa angloparlante, mi capacidad de distinguir acentos es limitada, así que necesito apoyo humano en la elección de voces del catálogo de ElevenLabs. Decidimos usar una declaración por asesinato, así que seleccionamos nueve voces cuyas diferencias de timbre y tono estructuran la secuencia y marcan su ritmo.

En un primer momento me empapé de los tutoriales de ElevenLabs para aprender cómo comunicarme con el software. Según el contenido del texto, buscaba una voz más o menos intensa, dramática, pausada o frenética. Intento no caer en la delegación creativa en la IA y lograr el resultado que le pediría a una persona. Con la práctica afino mis prompts y todo va más rápido. Mi sensación: la IA también aprende y se anticipa cada vez más a mis deseos.

Recapitulando, en este proyecto convive un ordenador viejo que se congela al abrir un PDF y una IA nuevecita que pone voz a declaraciones de 1986 con entonación natural y buena dicción. Es, al fin y al cabo, una metáfora del salto tecnológico y de la esquizofrenia de nuestro tiempo.

Dejo para la próxima entrega la tercera IA que estaba usando entonces para el documental: Midjourney. Les contaré cómo la utilicé para crear animaciones de algunas escenas de la vida del asesino.

English version (with a little of my friends Deepl and ChatGPT)

I was just trying to make a true crime about an ’80s serial killer

I replay it from memory, as if it were today—though all this happened a year and a half ago. In AI terms, that’s practically another era.

It’s Tuesday, May 28th, around 10:30 a.m. I’m in an apartment in Miami Beach, near Collins Avenue and 69th Street. I’ve been here for a few weeks, doing research with the team behind the documentary series I’m working on.

Right now, I have ChatGPT drafting outlines, summaries, lists, timelines… basically trying to bring some order to a chaos of documents upon documents—thousands of pages—that I feed it in controlled doses so it doesn’t overheat, poor thing.

Luckily, the Miami court had digitized case F86012910A. “F” stands for felony, “86” for the year. The file is split into about twenty volumes, each ranging from 300 to 2,000 pages. We had to go through the material right there, on a Jurassic computer running Windows Photo Viewer—page by page. I got scolded for daring to open Acrobat. That 64MB RAM wonder froze instantly. We had to reboot and resign ourselves to writing down, by hand, the page numbers that mattered.

We spent several days clicking—click, click, click—sorting through what wasn’t junk or duplication.

Then the archive staff reviewed our selection to remove any potentially sensitive information. They deleted a medical report ordered by the killer’s defense team for his final appeal, which was denied. He was executed by lethal injection in 2012. But by all means, let’s protect his medical privacy.

The truly surreal moment came next: the archive staff printed the selected documents, scanned them again, and handed them to us on a USB drive.

Some parts were already blurry in the first scan, since the papers were over twenty years old when they were digitized. After the re-scan of the printout of the scan, Acrobat’s OCR did what it could.

ChatGPT has standing orders to analyze everything and fill in the blanks using information from the new documents I keep adding. I set that up as a cross-task in the project’s initial prompt. I’m not sure it will keep following that instruction as the project grows, but I want to believe it will.

When I first started working with it, I thought: Isn’t this magical? My new best friend. I soon realized it’s a very imaginative friend. If you don’t set boundaries, it flies. It tells you what it thinks you want to hear. It makes things up. It lies to you.

Right now, it’s handling a specific task. I’ve shared all the affidavits from the police officers who responded to the crime scenes—quite detailed sworn statements of what they found. I’ve asked it to extract a timeline of all the victims, with descriptions of each crime scene, geolocation, officer’s name, and the full text of each statement.

That’s going to be the basis for a sequence presenting all the murders. The visuals will alternate between a map of Miami-Dade County—zooming in or out depending on each case—and images from the crime scenes. The voice-over will be a collage of fragments from the officers’ statements.

The second AI helping me with this first cut of the documentary: ElevenLabs’ voice synthesis software.

Its job is to bring voice to selected excerpts from those sworn statements. We’re giving sound to words that already exist—words that were probably first spoken among colleagues before being transcribed. In a way, we’re re-enacting that act of speaking them aloud.

The first time I generated a voice myself, I felt uneasy. Not because it sounded artificial, but because it didn’t. There were pauses, breaths, and a rhythm that felt almost always human. Occasionally a glitch or ghostly echo would pop up and make me jump. But what truly unsettled me was how realistic and convincing the audio sounded.

I quickly got used to working with these voices—not human, though cloned from real people’s voices, and not robotic either, since their core is a human recording with its tone and texture intact. To keep perspective, I remind myself these voices are just a medium for conveying meaning, just as actors’ voices would be if this sequence ever makes it to the final cut.

As a non-native English speaker, I’m not great at distinguishing accents, so I needed help choosing from ElevenLabs’ voice catalog. We decided to use one statement per murder, so we selected nine voices whose tonal and timbral differences structure the sequence and set its rhythm.

At first, I immersed myself in ElevenLabs’ tutorials to learn how to communicate with the software. Depending on the text, I wanted a voice more or less dramatic, slower or more frantic… I try not to hand over creative control to the AI and to aim for the same result I’d ask of a person. With practice, I fine-tune my prompts, and everything moves faster. My impression: the AI learns too, anticipating more and more what I want.

Looking back, this project brings together an old computer that freezes when opening a PDF and a brand-new AI that reads 1986 statements with natural tone and perfect diction. It’s, in the end, a metaphor for the technological leap—and the schizophrenia—of our time.

In the next installment, I’ll talk about the third AI I was using back then: Midjourney. I’ll share how I used it to create animations for a few scenes from the life of our protagonist.